Frank T. Merrill (1848-1923) was an American artist and illustrator. As an illustrator he was best remembered for illustrating Louisa May Alcott's Little Women in 1880.

Published 1887

The late Diedrich

Knickerbocker, an old gentleman of New York, who was very curious in the

Dutch history of the province, and the manners of the descendants from

its primitive settlers.

In that same village, and in one of these very houses (which, to tell

the precise truth, was sadly time-worn and weather-beaten), there lived

many years since, while the country was yet a province of Great Britain,

a simple, good-natured fellow, of the name of Rip Van Winkle.

The children of the village, too, would shout with joy whenever

he approached. He assisted at their sports, made their playthings,

taught them to fly kites and shoot marbles,....

A termagant

wife may, therefore, in some respects, be considered a tolerable

blessing; and if so, Rip Van Winkle was thrice blessed.

Fish all day without a murmur

He would never refuse to assist a neighbor even in the roughest

toil,....

He would carry a

fowling-piece on his shoulder for hours together, trudging through woods

and swamps, and up hill and down dale, to shoot a few squirrels or wild

pigeons.

His son Rip, an urchin begotten in his own likeness, promised to

inherit the habits, with the old clothes of his father.

...his cow would either go astray, or get

among the cabbages;...

For a long while

he used to console himself, when driven from home, by frequenting a kind

of perpetual club of the sages, philosophers, and other idle personages

of the village, which held its sessions on a bench before a small inn,

designated by a rubicund portrait of his majesty George the Third.

He shrugged his

shoulders, shook his head, cast up his eyes, but said nothing.

The moment Wolf entered the

house, his crest fell, his tail drooped to the ground, or curled between

his legs, he sneaked about with a gallows air, casting many a sidelong

glance at Dame Van Winkle, and at the least flourish of a broomstick or

ladle, he would fly to the door with yelping precipitation.

Here he would

sometimes seat himself at the foot of a tree, and share the contents of

his wallet with Wolf, with whom he sympathized as a fellow-sufferer in

persecution.

When anything that was read or related

displeased him, he was observed to smoke his pipe vehemently, and to

send forth short, frequent, and angry puffs; but when pleased, he would

inhale the smoke slowly and tranquilly, and emit it in light and placid

clouds, and sometimes taking the pipe from his mouth, and letting the

fragrant vapor curl about his nose, would gravely nod his head in token

of perfect approbation.

On the other side he looked down into a deep mountain glen, wild,

lonely, and shagged, the bottom filled with fragments from the impending

cliffs, and scarcely lighted by the reflected rays of the setting sun.

For some time Rip lay musing on this scene; evening was gradually

advancing; the mountains began to throw their long blue shadows over the

valleys; he saw that it would be dark long before he could reach the

village; and he heaved a heavy sigh when he thought of encountering the

terrors of Dame Van Winkle.

As he was about to descend he heard a voice from a distance hallooing,

“Rip Van Winkle! Rip Van Winkle!” He looked around, but could see

nothing but a crow winging its solitary flight across the mountain. He

thought his fancy 24

must have deceived him, and turned

again to descend, when he heard the same cry ring through the still

evening air, “Rip Van Winkle! Rip Van Winkle!”—at the same time Wolf

bristled up his back, and giving a low growl, skulked to his master’s

side, looking fearfully down into the glen.

On nearer approach, he was still more surprised at the singularity of

the stranger’s appearance. He was a short, square-built old fellow, with

thick bushy hair, and a grizzled beard. His dress was of the antique

Dutch fashion—a cloth jerkin strapped round the waist—several pair of

breeches, the outer one of ample volume, decorated with rows of buttons

down the sides, and bunches at the knees. He bore on his shoulders a

stout keg, that seemed full of liquor, and made signs for Rip to

approach and assist him with the load.

During

the whole time, Rip and his companion had labored on in silence; for

though the former marvelled greatly what could be the object of carrying

a keg of liquor up this wild mountain, yet there was something strange

and incomprehensible about the unknown, that inspired awe, and checked

familiarity.

On a level spot in the centre was a company of odd-looking

personages playing at nine-pins. They were dressed in a quaint

outlandish fashion: some wore short doublets, others jerkins, with long

knives in their belts, and most of them had enormous breeches, of

similar style with that of the guide’s. Their visages too, were

peculiar: one had a large head, broad face, and small piggish eyes; the

face of another seemed to consist entirely of nose, and was surmounted

by a white sugar-loaf hat, set off with a little red cock’s tail. They

all had beards, of various shapes and colors. There was one who

seemed to be the commander. He was a stout old

gentleman, with a weather-beaten countenance; he wore a laced doublet,

broad belt and hanger, high-crowned hat and feather, red stockings, and

high-heeled shoes, with roses in them. The whole group reminded Rip of

the figures in an old Flemish painting, in the parlor of Domine Van

Schaick, the village parson, and which had been brought over from

Holland at the time of the settlement.

There was one who

seemed to be the commander. He was a stout old

gentleman, with a weather-beaten countenance; he wore a laced doublet,

broad belt and hanger, high-crowned hat and feather, red stockings, and

high-heeled shoes, with roses in them.

He even ventured, when

no eye was fixed upon him, to taste the beverage, which he found had

much of the flavor of excellent Hollands. He was naturally a thirsty

soul, and was soon tempted to repeat the draught. One taste provoked

another, and he reiterated his visits to the flagon so often, that at

length his senses were overpowered, his eyes swam in his head, his head

gradually declined, and he fell into a deep sleep.

On waking, he found himself on the green knoll from whence he had first

seen the old man of the glen. He rubbed his eyes—it was

a bright sunny morning. ...He looked round for his gun, but in place of the clean well-oiled

fowling-piece, he found an old firelock lying by him, the barrel

encrusted with rust, the lock falling off, and the stock worm-eaten.

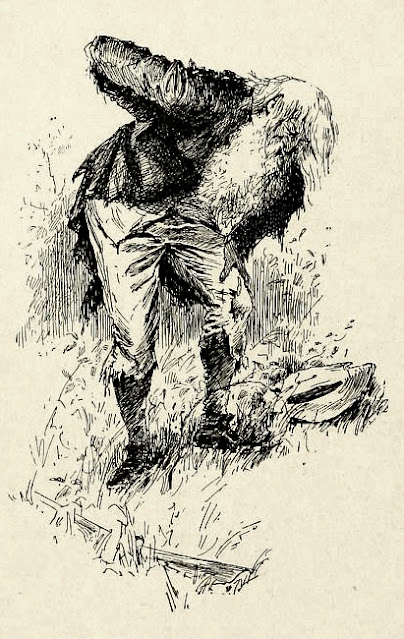

As he rose to

walk, he found himself stiff in the joints, and wanting in his usual

activity. “These mountain beds do not agree with me,” thought Rip, “and

if this frolic should lay me up with a fit of the rheumatism, I shall

have a blessed time with Dame Van Winkle.”

He again called and whistled after his

dog; he was only answered by the cawing of a flock of idle crows,

sporting high in the air about a dry tree that overhung a sunny

precipice;...

As he approached the village, he met a number of people, but none whom

he knew, which somewhat surprised him, for he had thought himself

acquainted with every one in the country round. Their dress, too, was of

a different fashion from that to which he was accustomed. They all

stared at him with equal marks of surprise, and whenever they cast eyes

upon him, invariably stroked their chins. The constant recurrence of

this gesture induced Rip, involuntarily, to do the same, when, to his

astonishment, he found his beard had grown a foot long!

He had now entered the skirts of the village. A troop of strange

children ran at his heels, hooting after him, and pointing at his gray

beard. The dogs, too, not one of which he recognized for an old

acquaintance, barked at him as he passed. The very village was altered:

it was larger and more populous.

A

half-starved dog, that looked like Wolf, was skulking about it. Rip

called him by name, but the cur snarled, showed his teeth, and passed

on. This was an unkind cut indeed.—“My very dog,” sighed poor Rip, “has

forgotten me!”

He

recognized on the sign, however, the ruby face of King George, under

which he had smoked so many a peaceful pipe, but even this was

singularly metamorphosed.

There was, as usual, a crowd of folk about the door, but none that Rip

recollected. The very character of the people seemed changed. There was

a busy, bustling, disputatious tone about it,

instead

of the accustomed phlegm and drowsy tranquillity.

The appearance of Rip, with his long, grizzled beard, his rusty

fowling-piece, his uncouth dress, and the army of women and children

that had gathered at his heels, soon attracted the attention of the

tavern politicians. They crowded round him, eyeing him from head to

foot, with great curiosity. The orator bustled up to him, and drawing

him partly aside, inquired, “on which side he voted?” Rip stared in

vacant stupidity.

“Where’s Brom Dutcher?”

“Oh, he went off to the army in the beginning of the war; some say he

was killed at the storming of Stony-Point—others say he was drowned in

the squall, at the foot of Antony’s Nose. I don’t know—he never came

back again.”

“Where’s Van Bummel, the schoolmaster?”

“He went off to the wars, too; was a great militia general, and is now

in Congress.”

“Oh, Rip Van Winkle!” exclaimed two or three. “Oh, to be sure! that’s

Rip Van Winkle yonder, leaning against the tree.”

Rip looked, and beheld a precise counterpart of himself as he went up

the mountain; apparently as lazy, and certainly as ragged. The poor

fellow was now completely confounded. He doubted his own identity, and

whether he was himself or another man. In the midst of his bewilderment,

the man in the cocked hat demanded who he was, and what was his name?

“What is your name, my good woman?” asked he.

“Judith Gardenier.”

“And your father’s name?”

“Ah, poor man, his name was Rip Van Winkle; it’s twenty years since he

went away from home with his gun, and never has been heard of since—his

dog came home without him; but whether he shot himself, or was carried

away by the Indians, nobody can tell. I was then but a little girl.”

There was a drop of comfort, at least, in this intelligence. The honest

man could contain himself no longer. He caught his daughter and her

child in his arms. “I am your father!” cried he—“Young Rip Van Winkle

once—old Rip Van Winkle now—Does nobody know poor Rip Van Winkle!”

It was determined, however, to take the opinion of old Peter Vanderdonk,

who was seen slowly advancing up the road. He was a descendant of the

historian of that name, who

wrote one of the earliest accounts of the

province. Peter was the most ancient inhabitant of the village, and well

versed in all the wonderful events and traditions of the neighborhood.

He recollected Rip at once, and corroborated his story in the most

satisfactory manner.

Rip now resumed his old walks and habits; he soon found many of his

former cronies, though all rather the worse for the wear and tear of

time; and preferred making friends among the rising generation, with

whom he soon grew into great favor.

Having nothing to do at home, and being arrived at that happy age when a

man can do nothing with impunity, he took his place once more on the

bench, at the inn door, and was reverenced as one of the patriarchs of

the village, and a chronicle of the old times “before the war.”

Rip, in fact, was no politician; the changes of

states and empires made but little impression on

him; but there was one

species of despotism under which he had long groaned, and that

was—petticoat government. Happily, that was at an end; he had got his

neck out of the yoke of matrimony, and could go in and out whenever he

pleased, without dreading the tyranny of Dame Van Winkle. Whenever her

name was mentioned, however, he shook his head, shrugged his shoulders,

and cast up his eyes; which might pass either for an expression of

resignation to his fate, or joy at his deliverance.