Claude

Allin Shepperson (1867-1921) was a British artist and illustrator. He

trained at Heatherley's and in Paris and was one of a

number of illustrators who worked as a tutor at Percy Bradshaw's Press Art School. Working in most

media, Shepperson's pictures are a masterclass in elegance, grace and

refinement, and scene of high society, often featuring the 'Shepperson Girl,'

were his speciality. He contributed regularly to TheTatler magazine, the ideal

magazine to showcase his work. He illustrated H.G. Well's The First Men in the Moon which was first published in The Strand Magazine 1900 - 1901. A book edition was published in 1901. However, in the book edition only 13 illustrations from The Strand Magaazine were shown.

The First Men in the Moon in The Strand Magazine

I. — MR. BEDFORD MEETS

MR. CAVOR AT LYMPNE

I soon discovered that writing a play was a longer business than

I had supposed; at first I had reckoned ten days for it, and it was

to have a pied-à-terre while it was in hand that I came to

Lympne.

He was a short, round-bodied, thin-legged little man, with a

jerky quality in his motions; he had seen fit to clothe his

extraordinary mind in a cricket cap, an overcoat, and cycling

knickerbockers and stockings. Why he did so I do not know, for he

never cycled and he never played cricket. It was a fortuitous

concurrence of garments, arising I know not how. He gesticulated

with his hands and arms, and jerked his head about and buzzed. He

buzzed like something electric. You never heard such buzzing. And

ever and again he cleared his throat with a most extraordinary

noise.

Then

with a sort of convulsive gesture he turned and retreated with

every manifestation of haste, no longer gesticulating, but going

with ample strides that showed the relatively large size of his

feet—they were, I remember, grotesquely exaggerated in size

by adhesive clay—to the best possible advantage.

He was quite willing to supply information. Indeed, once he was

fairly under way the conversation became a monologue. He talked

like a man long pent up, who has had it over with himself again and

again. He talked for nearly an hour, and I must confess I found it

a pretty stiff bit of listening.

"I begin to see. It's extraordinary how one gets

new points of view by talking over things!"

II. — THE FIRST MAKING

OF CAVORITE

Instantly my coat tails were over my head, and I was progressing

in great leaps and bounds, and quite against my will, towards him.

In the same moment the discoverer was seized, whirled about, and

flew through the screaming air.

I repeated my suggestion of getting back to my bungalow, and

this time he understood. We clung arm-in-arm and started, and

managed at last to reach the shelter of as much roof as was left to

me.

III. — THE BUILDING OF

THE SPHERE

And while he was having his bath I considered the entire

question alone.

An extraordinary possibility came rushing into my mind. Suddenly

I saw, as in a vision, the whole solar system threaded with

Cavorite liners and spheres deluxe. "Rights of pre-emption," came

floating into my head—planetary rights of pre-emption. I

recalled the old Spanish monopoly in American gold.

At last I got back to bed and snatched some moments of

sleep—moments of nightmare rather—in which I fell and

fell and fell for evermore into the abyss of the sky.

IV. — INSIDE THE

SPHERE

"Go on," said Cavor, as I sat across the edge of

the manhole, and looked down into the black interior of the sphere.

We two were alone. It was evening, the sun had set, and the

stillness of the twilight was upon everything.

V. — THE JOURNEY TO THE

MOON

The little window vanished with a click, another beside it

snapped open and instantly closed, and then a third, and for a

moment I had to close my eyes because of the blinding splendour of

the waning moon.

And as I stood and

stared at the moon between my feet, that perception of the

impossible that had been with me off and on ever since our start,

returned again with tenfold conviction.

Presently he told me he wished to alter our course a little by

letting the earth tug at us for a moment. He was going to open one

earthward blind for thirty seconds. He warned me that it would make

my head swim, and advised me to extend my hands against the glass

to break my fall. I did as he directed, and thrust my feet against

the bales of food cases and air cylinders to prevent their falling

upon me. Then with a click the window flew open. I fell clumsily

upon hands and face, and saw for a moment between my black extended

fingers our mother earth—a planet in a downward sky.

VI. — THE LANDING ON THE

MOON

Then Cavor switched on the electric light, and told me he

proposed to bind all our luggage together with the blankets about

it, against the concussion of our descent. We did this with our

windows closed, because in that way our goods arranged themselves

naturally at the centre of the sphere. That too was a strange

business; we two men floating loose in that spherical space, and

packing and pulling ropes.

We were still alive, and we were lying in the darkness of the

shadow of the wall of the great crater into which we had

fallen.

VII. — SUNRISE ON THE

MOON

Then some huge landslip in the thawing air had caught us, and

spluttering expostulation, we began to roll down a slope, rolling

faster and faster, leaping crevasses and rebounding from banks,

faster and faster, westward into the white-hot boiling tumult of

the lunar day.

VIII. A LUNAR MORNING

"Life!" And immediately it poured upon us that our vast journey

had not been made in vain, that we had come to no arid waste of

minerals, but to a world that lived and moved! We watched

intensely. I remember I kept rubbing the glass before me with my

sleeve, jealous of the faintest suspicion of mist.

IX. PROSPECTING

BEGINS

He

seemed twenty or thirty feet off. He was standing high upon a rocky

mass and gesticulating back to me. Perhaps he was

shouting—but the sound did not reach me. But how the deuce

had he done this? I felt like a man who has just seen a new

conjuring trick.

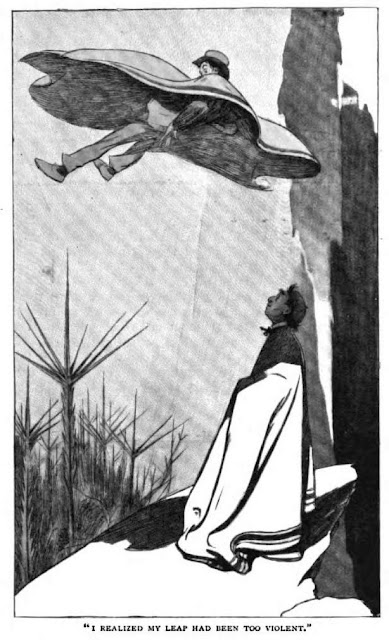

It was horrible and delightful, and as wild as a nightmare, to

go flying off in this fashion. I realised my leap had been

altogether too violent. I flew clean over Cavor's head and beheld a

spiky confusion in a gully spreading to meet my fall. I gave a yelp

of alarm. I put out my hands and straightened my legs.

I stood for a moment

struck by the grotesque effect of his soaring figure—his

dirty cricket cap, and spiky hair, his little round body, his arms

and his knicker-bockered legs tucked up tightly—against the

weird spaciousness of the lunar scene.

X. — LOST MEN IN THE

MOON

Boom... Boom... Boom.

It came from beneath our feet, a sound in the earth. We seemed

to hear it with our feet as much as with our ears. Its dull

resonance was muffled by distance, thick with the quality of

intervening substance. No sound that I can imagine could have

astonished us more, or have changed more completely the quality of

things about us. For this sound, rich, slow, and deliberate, seemed

to us as though it could be nothing but the striking of some

gigantic buried clock.

XI. — THE MOONCALF

PASTURES

A crackling and smashing of the scrub appeared to be advancing

directly upon us, and then, as we squatted close and endeavoured to

judge of the nearness and direction of this noise, there came a

terrific bellow behind us, so close and vehement that the tops of

the bayonet scrub bent before it, and one felt the breath of it hot

and moist. And, turning about, we saw indistinctly through a crowd

of swaying stems the mooncalf's shining sides, and the long line of

its back loomed out against the sky.

He had been a little distance from the edge when the

lid had first opened, and perceiving the peril that held me

helpless, gripped my legs and pulled me backward.

He stood

up as well as he could, putting a hand on my head to steady

himself, which was disrespectful, and stood staring about him,

quite devoid now of any fear of the moon beings.

Almost immediately we must have come upon the Selenites. There

were six of them, and they were marching in single file over a

rocky place, making the most remarkable piping and whining sounds.

They all seemed to become aware of us at once, all instantly became

silent and motionless, like animals, with their faces turned

towards us.

For a moment I was sobered.

"Insects," murmured Cavor, "insects! And they think I'm going to

crawl about on my stomach—on my vertebrated stomach!

XII. — THE SELENITE'S

FACE

There was no nose, and the thing had dull bulging eyes

at the side—in the silhouette I had supposed they were ears.

There were no ears... I have tried to draw one of these heads, but

I cannot. There was a mouth, downwardly curved, like a human mouth

in a face that stares ferociously...

The neck on which the head was poised was jointed in three

places, almost like the short joints in the leg of a crab. The

joints of the limbs I could not see, because of the puttee-like

straps in which they were swathed, and which formed the only

clothing the being wore.

There the thing was, looking at us!

XIII. MR. CAVOR MAKES

SOME SUGGESTIONS

He paused as if he required my assent. But I sat sulking.

"Confound your science!" I said.

I perceived that the foremost and second carried bowls.

One elemental need at least our minds could understand in common.

They were bowls of some metal that, like our fetters, looked dark

in that bluish light; and each contained a number of whitish

fragments. All the cloudy pain and misery that oppressed me rushed

together and took the shape of hunger. I eyed these bowls

wolfishly, and, though it returned to me in dreams, at that time it

seemed a small matter that at the end of the arms that lowered one

towards me were not hands, but a sort of flap and thumb, like the

end of an elephant's trunk.

XIV. EXPERIMENTS IN

INTERCOURSE

We remained passive, and the Selenites, having finished their

arrangements, stood back from us, and seemed to be looking at us. I

say seemed to be, because as their eyes were at the side and not in

front, one had the same difficulty in determining the direction in

which they were looking as one has in the case of a hen or a fish.

I turned on the goad-bearer behind me with a swift threatening

gesture, and he started back. This and Cavor's sudden shout and

leap clearly astonished all the Selenites. They receded hastily,

facing us. For one of those moments that seem to last for ever, we

stood in angry protest, with a scattered semicircle of these

inhuman beings about us.

XV. THE GIDDY

BRIDGE

We seemed to be marching down that tunnel for a long time.

"Trickle, trickle," went the flowing light very softly, and our

footfalls and their echoes made an irregular paddle, paddle. My

mind settled down to the question of my chains. If I were to slip

off one turn

so, and then to twist it

so...

My mailed hand seemed to go clean through him. He smashed

like—like some softish sort of sweet with liquid in it! He

broke right in! He squelched and splashed. It was like hitting a

damp toadstool.

I stopped and looked back, and I heard the pad, pad of Cavor's

feet receding. Then he stopped also. "Bedford," he whispered;

"there's a sort of light in front of us."

XVI. POINTS OF

VIEW

I plucked up half a dozen and flung them against the rocks,

and then sat down, laughing bitterly, as Cavor's ruddy face came

into view.

At any rate, we had now

the comforting knowledge of the enormous muscular superiority our

birth in another planet gave us. In other minute I was clambering

with gigantic vigour after Cavor's blue-lit heels.

XVII. THE FIGHT IN THE

CAVE OF THE MOON BUTCHERS

And lying in a

line along its length, vanishing at last far away in that

tremendous perspective, were a number of huge shapes, huge pallid

hulls, upon which the Selenites were busy.

I realised Cavor's utter incapacity for the fight we had in

hand. For a moment I hesitated. Then I rushed past him whirling my

crowbars, and shouting to confound the aim of the Selenite. He was

aiming in the queerest way with the thing against his stomach.

"Chuzz!" The thing wasn't a gun; it went off like cross-bow more,

and dropped me in the middle of a leap.

I remember I seemed to be wading among those

leathery, thin things as a man wades through tall grass, mowing and

hitting, first right, then left; smash. Little drops of moisture

flew about. I trod on things that crushed and piped and went

slippery.

XVIII. IN THE

SUNLIGHT

I stood up. "We must get a fixed point we can recognise—we

might hoist a flag, or a handkerchief, or something—and

quarter the ground, and work round that."

I was on the

point of asking him to shake hands—for that, somehow, was how

I felt just then—when he put his feet together and leapt away

from me towards the north. He seemed to drift through the air as a

dead leaf would do, fell lightly, and leapt again. I stood for a

moment watching him, then faced westward reluctantly, pulled myself

together, and with something of the feeling of a man who leaps into

icy water, selected a leaping point, and plunged forward to explore

my solitary half of the moon world.

XIX. MR. BEDFORD

ALONE

I could see my handkerchief far off, spread out on

its thicket of thorns.

I saw the sphere!...

I threw up my arms, shouted a ghostly shout, and set off in vast

leaps towards it. I missed one of my leaps and dropped into a deep

ravine and twisted my ankle, and after that I stumbled at almost

every leap. I was in a state of hysterical agitation, trembling

violently, and quite breathless long before I got to it.

I set myself to decipher this.

"I have been injured about the knee, I think my kneecap is hurt,

and I cannot run or crawl," it began—pretty distinctly

written.

Then less legibly: "They have been chasing me for some time, and

it is only a question of"—the word "time" seemed to have been

written here and erased in favour of something

illegible—"before they get me. They are beating all about

me."

I was a dozen yards from it. My eyes had become dim. "Lie down!"

screamed despair; "lie down!"

I touched it, and halted. "Too late!" screamed despair; "lie

down!"

I fought stiffly with it. I was on the manhole lip, a stupefied,

half-dead being. The snow was all about me. I pulled myself in.

There lurked within a little warmer air.

XX. MR. BEDFORD IN

INFINITE SPACE

I was in darkness, save for the

earthshine and the glitter of the stars below me. Everything was so

absolutely silent and still that I might indeed have been the only

being in the universe, and yet, strangely enough, I had no more

feeling of loneliness or fear than if I had been lying in bed on

earth.

XXI. MR. BEDFORD AT

LITTLESTONE

The sphere hit the water with a huge splash: it must have sent

it fathoms high. At the splash I flung the Cavorite shutters open.

Down I went, but slower and slower, and then I felt the sphere

pressing against my feet, and so drove up again as a bubble drives.

And at the last I was floating and rocking upon the surface of the

sea, and my journey in space was at an end.

"I want help," I said hoarsely. "I want to get some

stuff up the beach—stuff I can't very well leave about." I

became aware of three other pleasant-looking young men with towels,

blazers, and straw hats, coming down the sands towards me.

Evidently the early bathing section of this Littlestone.

The sea, which had been smooth, was rough now with hurrying

cat's-paws, and all about where the sphere had been was tumbled

water like the wake of a ship. Above, a little puff of cloud

whirled like dispersing smoke, and the three or four people on the

beach were bring up with interrogative faces towards the point of

that unexpected report.

I gesticulated convulsively. He receded a step as though I had

threatened him. I made a bolt through them into the hotel.

XXII. THE ASTONISHING

COMMUNICATION OF MR. JULIUS WENDIGEE

...there reached me (it is now about six months

ago) one of the most astounding communications I have ever been

fated to receive. Briefly, it informed me that Mr. Julius Wendigee,

a Dutch electrician, who has been experimenting with certain

apparatus akin to the apparatus used by Mr. Tesla in America, in

the hope of discovering some method of communication with Mars, was

receiving day by day a curiously fragmentary message in English,

which was indisputably emanating from Mr. Cavor in the moon.

XXIII. AN ABSTRACT OF

THE SIX MESSAGES

FIRST RECEIVED FROM MR. CAVOR

And at last far below him he

saw, as it were, a lake of heatless fire, the waters of the Central

Sea, glowing and eddying in strange perturbation, "like luminous

blue milk that is just on the boil."

As they pulled at it that net seemed the

heaviest thing I had come upon in the moon; it was loaded with

weights—no doubt of gold—and it took a long time to

draw, for in those waters the larger and more edible fish lurk

deep. The fish in the net came up like a blue moonrise—a

blaze of darting, tossing blue.

XXIV. THE NATURAL

HISTORY OF THE SELENITES

Finding he would not walk even under the goad, they carried him

into darkness, crossed a narrow, plank-like bridge that may have

been the identical bridge I had refused, and put him down in

something that must have seemed at first to be some sort of lift.

This was the balloon—it had certainly been absolutely

invisible to us in the darkness—and what had seemed to me a

mere plank-walking into the void was really, no doubt, the passage

of the gangway.

"It was an incredible crowd. Suddenly and violently there was

forced upon my attention the vast amount of difference there is

amongst these beings of the moon.

"Indeed, there seemed not two alike in all that jostling

multitude. They differed in shape, they differed in size, they rang

all the horrible changes on the theme of Selenite form! Some bulged

and overhung, some ran about among the feet of their fellows.

He seems to have grasped their intention

with great quickness, and to have begun repeating words to them and

pointing to indicate the application. The procedure was probably

always the same. Phi-oo would attend to Cavor for a space, then

point also and say the word he had heard.

...but some of the profounder scholars are altogether

too great for locomotion, and are carried from place to place in a

sort of sedan tub, wabbling jellies of knowledge that enlist my

respectful astonishment. I have just passed one in coming to this

place where I am permitted to amuse myself with these electrical

toys, a vast, shaven, shaky head, bald and thin-skinned, carried on

his grotesque stretcher.

One, I

remember very distinctly: he left a strong impression, I think,

because some trick the light and of his attitude was strongly

suggestive a drawn-up human figure. His fore-limbs were long,

delicate tentacles—he was some kind of refined

manipulator—and the pose of his slumber suggested a

submissive suffering. No doubt it was a mistake for me to interpret

his expression in that way,...

XXV. THE GRAND

LUNAR

"In front, after the manner of heralds, marched four

trumpet-faced creatures making a devastating bray; and then came

squat, resolute-moving ushers before and behind, and on either hand

a galaxy of learned heads, a sort of animated encyclopedia, who

were, Phi-oo explained, to stand about the Grand Lunar for purposes

of reference.

Higher and higher these steps appear to go as one draws nearer

their base. But at last I came under a huge archway and beheld the

summit of these steps, and upon it the Grand Lunar exalted on his

throne.

"He was seated in what was relatively a blaze of incandescent

blue. This, and the darkness about him gave him an effect of

floating in a blue-black void. He seemed a small, self-luminous

cloud at first, brooding on his sombre throne; his brain case must

have measured many yards in diameter.

I became aware of a faint wheezy noise. The Grand Lunar was

addressing me. It was like the rubbing of a finger upon a pane of

glass.

"The iris was quite a new organ to the Grand Lunar. For a time

he amused himself by flashing his rays into my face and watching my

pupils contract. As a consequence, I was dazzled and blinded for

some little time...

When I had done he ordered cooling sprays upon his brow, and

then requested me to repeat my explanation conceiving something had

miscarried.

I told, too, of the past, of invasions and massacres, of the

Huns and Tartars, and the wars of Mahomet and the Caliphs, and of

the Crusades. And as I went on, and Phi-oo translated, and the

Selenites cooed and murmured in a steadily intensified emotion.

XXVI. THE LAST MESSAGE

CAVOR SENT TO THE EARTH

For my own part a

vivid dream has come to my help, and I see, almost as plainly as

though I had seen it in actual fact, a blue-lit shadowy dishevelled

Cavor struggling in the grip of these insect Selenites, struggling

ever more desperately and hopelessly as they press upon him,

shouting, expostulating, perhaps even at last fighting, and being

forced backwards step by step out of all speech or sign of his

fellows, for evermore into the Unknown—into the dark, into

that silence that has no end...

END

Wir zeigen hier noch die Buchillustrationen, da sie etwas besser sind als diejenigen im Strand-Magazin.